CLOSE

Cancel

Growing up Korean American, Seollal (Lunar New Year) was one of the most exciting and meaningful times of the year. It has been a bridge that connects me to my cultural roots while allowing me to understand the traditions my parents continue to cherish to this day.

Each part of the day, such as performing Saebae, eating Tteokguk and playing Yutnori, has special significance and traditions that I will carry with me and share with the next generation. In a world where cultures can blend and change, I slow down and cherish these moments of authenticity by honoring my heritage and sharing it with others.

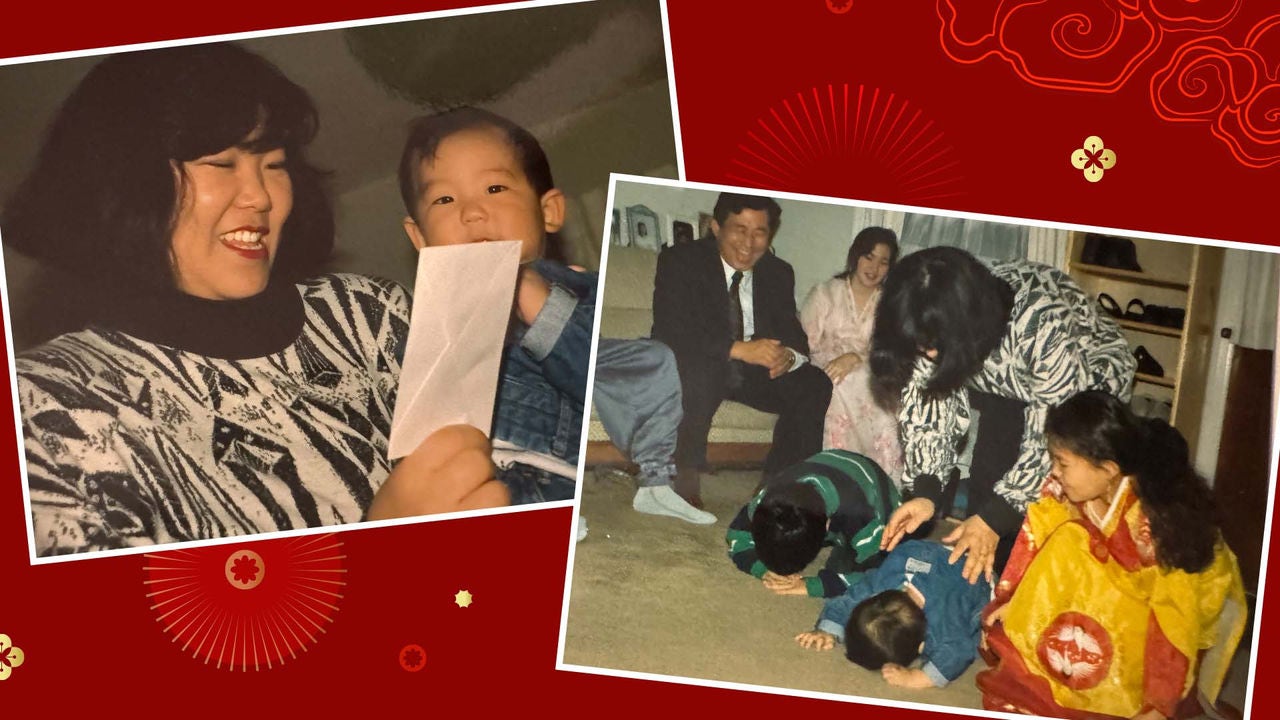

The morning of Seollal always begins with Saebae, a deep bow to pay respect to our elders and to wish them a year filled with blessings and good health.

When I was younger, I never really understood the significance behind the bow other than knowing there was a money envelope at the end of the gesture. I remember fumbling awkwardly to kneel properly and mumbled through the phase “새해 복 많이 받으세요” (saehae bok mani badeuseyo).

As I have gotten older, I have learned the significance of Saebae, as it is not just a financial transaction, but a way of honoring the ties between generations and paying respect, gratitude, and love for those who have come before us.

No Seollal is complete without a bowl of Tteokguk, rice cake soup. My mom explained that eating it symbolizes growing older by one year. As a child, I eagerly polished off my bowl and jokingly asked for seconds to “age faster.”

The soup itself is simple yet comforting: a clear beef broth filled with thinly sliced tteok, topped with egg ribbons, seaweed and green onions. While the ingredients were familiar, the act of eating it during Seollal feels ceremonial. It isn’t just food, it’s tradition. Now when I cook Tteokguk myself, I’m reminded of the conversations we had around the table sharing hopes for the year ahead.

After the formalities and meals comes Yutnori, the traditional Korean board game that brings out everyone’s competitive side.

My family and I would sit cross-legged on the floor throwing the four yut sticks into the air with a loud clatter. Would they land do (one step), gae (two steps), or better yet, yut (four steps)?

Strategies are whispered, alliances are formed, and room echoes with laughter and good-natured banter. It amazes me that such a simple game can bring everyone together like this.

For me, Seollal is more than a celebration. It’s a day that connects me to my identity as a Korean American. It’s a reminder that our traditions aren’t just customs, they are stories passed down through generations.

Even as life gets busier and I’m further away from my family, these rituals ground me, reminding me of where I come from and the legacy I carry forward.

James Lee joined The Hershey Company in 2015. He currently works as the Regional Sales Leader in Cincinnati, Ohio.